I think I'm at the point where I need to jot something down that can serve as a straw man statement. I've been putting some portfolios together and I need an organizational metaphor to give my work context.

Looking around at other photographers' sites, here are some excerpts from artist statements:

John Langmaid writes: "As a photographer of natural landscape and wildlife scenes, I seek to communicate my visual perception of a time and place. I attempt to capture my eyes' image in a photograph that possesses sufficient scale and fidelity so that the viewer can look into the print and experience that visual moment."

Alicia Sparaco writes: "I believe a successful artist never "captures" a moment but actually "releases" it to others. With my photography, (both black & white and Polaroid) I strive to transcend the documentary nature of the format by the sheer force of the experience. My work is both reflection and expression in that I do not aim or plan a shot, but instead allow myself to be found within it as it occurs. There is neither prior preparation nor postproduction with my black and white stills. What you see is what is happening as it happens. The only special effect or sense of majik is the one I am caught up in as the moment forms. The only illusion is the memory of that flash in time. I play in the field and frame of what is to become a picture. It's as simple as that."

Joe Braun writes: "Okay... This is my little narcissistic page where I get to talk about myself for a few paragraphs. Many photographers have grandiose statements about art, spirituality, and the symbolism of the universe. In comparison, my aesthetic is very simple and straight-forward: try to capture interesting places and moments in time and make them as beautiful as possible. Since we can't always be in the places we love, we can at least take the image of them with us to remember and share with others. (Oh wait... that does sound a bit grandiose.)"

And, of course, Ed Burtynsky writes: "Nature transformed through industry is a predominant theme in my work. I set course to intersect with a contemporary view of the great ages of man; from stone, to minerals, oil, transportation, silicon, and so on. To make these ideas visible I search for subjects that are rich in detail and scale yet open in their meaning. Recycling yards, mine tailings, quarries, and refineries are all places that are outside of our normal experience, yet we partake of their output on a daily basis.

These images are meant as metaphors to the dilemma of our modern existence; they search for a dialogue between attraction and repulsion, seduction and fear. We are drawn by desire — a chance at good living, yet we are consciously or unconsciously aware that the world is suffering for our success. Our dependence on nature to provide the materials for our consumption and our concern for the health of our planet set us into an uneasy contradiction. For me, these images function as reflecting pools of our times."

There are a couple of styles of statements emerging. There is the photographer who seeks purity. Let's call this the "what you see is what you get" or "moment in time" school of thought. The extremists claim to avoid digital manipulation of images. Then, there is the "image as deep metaphor" school. Where do I want to fit on this continuum?

Despite my natural aversion to pretension, I'm much more in Burtynsky's camp. If a photograph or a series of photographs is worthy of being called fine art, then it ought to be more than just a moment captured in time, even though the moment may have been a good one.

So, here's draft one of my artist's statement, where my intention is to guide the kinds of portfolios I do and the kinds of shots I pursue.

Huw Morgan: Artist's Statement - draft

There is a duality to light as well as life. Light can be thought of as a stream of particles or as a beam of waves. Life can also be thought of as a collection of static moments and objects or as a set of repetitive cycles that resemble waves. Think of the seasons, the cycles of life, the rising and setting of the sun, the daily routines of work and home life.

My intent is to use light, through photography and digital image manipulation, to capture the sense of life as part of a soothing, universal rhythm. All moments caught in the camera are part of a continuum of time and suggest what has gone before and what will happen after. Often these moments are bittersweet, like the beautiful seed pod caught in that moment of explosion when its seeds are released to the wind where they will start the cycle of life anew. Or the face of a person nearing the end of a lifespan, with the question of life after death hanging in the air. Or even the beauty in a rusty door on a building awaiting urban renewal.

My intent is to create a series of portfolios that capture life as wave. My first project was to capture the beauty in the decay of berries and seed pods as fall becomes winter, then spring. My second project, currently under way, is to capture large lake freighters locked in harbour ice, waiting for the spring melt. The possibilities are endless.

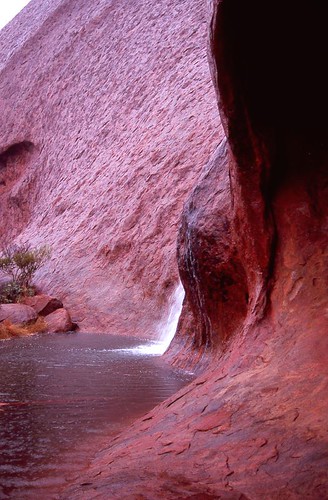

Here's an image from my first portfolio: